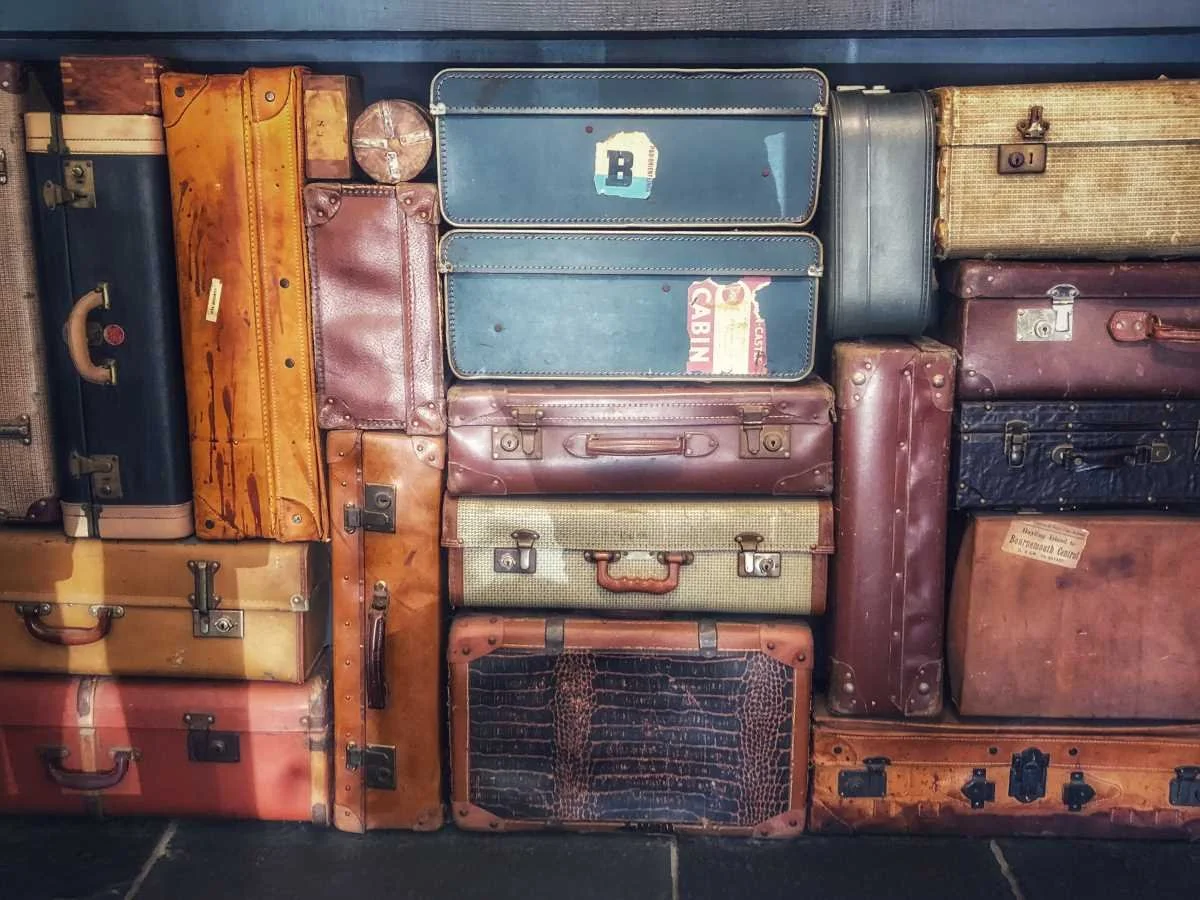

Suitcases and Scenes

We’re on a journey. We’re not sure of exactly where we’re headed and so are equally unsure of what to pack. What if we add to this adventure the promise that wherever we choose to stop traveling for a day, at the beginning of the next, we’ll find a freshly packed suitcase. This new case will have the necessities for where we are at this point in our travels: Reminders of what we experienced in reaching here; what we’ll encounter today; and hints of what we’ll need further down the road—like an umbrella. We start to feel as though our unknown destination is packing for us. Wouldn’t such a service make getting there feel more certain, giving us an arrival that lands as if we’ve known the end point all along?

Such a service does exist in a carefully wrought story. Our suitcase in the moment is whatever scene we are currently reading—or writing. A well-packed scene provides both the security and surprise a good story delivers. What do writers get for their effort in composing each new scene? Security and surprise. Confidence arises from work.

Writing is a transformative experience, an abundance of choice and change. Form doesn’t matter on this point. Be it poetry or memoir or fiction or nonfiction or a hybrid, without a story centered in changing—or not changing—no one has anything of substance to write. Reliably, first sentences prove difficult because that first line is where we step out of our comfort zones into the big, wildly unpredictable world to forge new paths from words. What we pack in the first suitcase, our opening scene, is important to our journey until it becomes unimportant. We may not understand its unimportance until the end of the trip when we realize we over-packed in the beginning.

Our work then becomes correctly packing each suitcase-scene for the reader’s current point in the story.

Our work then becomes correctly packing each suitcase-scene for the reader’s current point in the story. We must focus on what the reader needs: details and action that bring together what the reader already knows; added details and action required at the present point; hints of details and action not yet relevant yet needed to reach the hazy but irresistible sense of an end. Done well, the reader can feel that end growing closer with every scene. The best endings pull the reader toward them in a fever of curiosity. What’s in the next suitcase?

We must first take these journeys ourselves. We’re the first readers of our own work. Until we reach the completion of a first draft, we won’t really have a sense of what each scene needs or doesn’t need—if the scene itself is even needed. Adding unnecessary luggage to a journey doesn’t endear anyone to the tour guide. A person can carry only so much.

What is in a well-packed scene? As mentioned earlier, details and action. The more concrete the detail, the more sensory the description, the bigger the emotional impact on the reader. We choose our details carefully. Stories call for telling details. We need to be able to convey the significance of the amber color of the vase holding the wilting daisies without saying directly the color reminds the character of the amber pendant her estranged mother used to wear.

Showing why the vase’s color is meaningful depends on how the detail rises in relation to the action. Action includes not only what people or characters do, but dialogue, setting, pacing, narrative time management, plot, structure, and every other element that serves to move the story toward its end by showing the significance of the telling details through characters’ (or images’ or people’s) actions.

To this writer’s sorrow, she’s yet to find a magically repacking suitcase. Packing requires planning and risk and choice—as do scenes. Scenes give us the opportunity to renew and refresh the reader’s understanding about where they are and what to notice in the story’s travel plans. That’s how a narrative gains its sense of movement between here and there.

Writing Exercise

Let’s try a little unpacking here. Choose a scene from a book or film you admire. Read or watch it twice or more (maybe once aloud). Make a list of the concrete details used in the scene. Next make a list of the sensory descriptions of each detail. Finally write, for one or more element of what you noticed: 1) How it makes you, the reader feel, and 2) how you believe it matters to the story as a whole. This is not a question of being right or wrong. This is an exercise in noticing what is important to the story and why. Bonus Points: include in your list making the actions sparked by the given details in this scene.

Photo by Belinda Fewings on Unsplash